This project is unlike the majority of Wilderness Volunteers projects. Most WV projects will have the same base camp for the entire week. Volunteers might meet the afternoon preceding their first official project day, but once you’ve established your basecamp, that’s it for the entire work week.

If you want to come eye to eye with the might of natural forces, come to the KRNCA. When you’re not praying to whatever higher power that it doesn’t dump rain on you or blow that precipitation sideways, you may find yourself slack-jawed when you come across parts of the trail that have been eroded during insanely powerful winter storms. The shoreline is decorated with giant trees haphazardly strewn about; bold lines of debris tell the quiet and powerful stories of winter storms past.

With the powerful winter storms, winds and waves that batter the coastline, every spring brings a new offering of discovered destruction. During a beach clean up, half of our team hiked to Randall Creek and were asked by Devan to take recon pictures of the creek mouth feeding into the ocean. Hikers and even sometimes volunteers end up being valuable eyes for the BLM, as they provide real-time information about trail conditions and dangers.

One of the tasks our volunteer group was assigned was to pick up trash along the beach and on the bluff. What might seem like a banal activity soon became a fun and obsessive pastime. Our group found countless interesting pieces of trash, tons of rope, buoys, a refrigerator, a wheel and tire, 3 ammo boxes, and tons more. The thing that stuck with me was the amount of single-use plastic we retrieved. Water bottles were the main culprit, but we frequently came across food packaging, gallons jugs, and flip flops. I do believe if people saw the volume of the trash, specifically single-use plastics, we retrieved in just a sliver of shoreline, they might at least recall this the next time they’re faced with deciding to use single-use plastics.

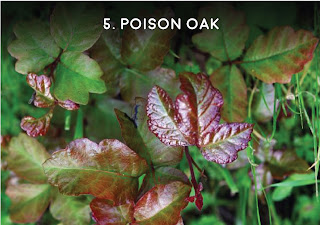

I had heard whispers about the poison oak to be found in King Range. Simple chatter. I’ve grown up around it but I still didn’t know what to expect. While the concern is real, the exposure is manageable. Our team was highly aware and very communicative if we spotted it. We were cautious about where we were walking, working, where we placed our tools, backpacks, etc. We were mindful to keep any possible oil exposed articles of clothing, shoes, and gloves separate from our clean gear. This project also taught me that poison oak will gladly share your most scenic, sandy stretches of beach with you. Never let your guard down. Thankfully, we only had one participant who experienced exposure and to their credit, they came into the field with Tecnu (a soap designed specifically to remove poison oak/ivy oils).

This was a big safety discussion during our briefing for our project. Don’t turn your back to the ocean, don’t go swimming and always be on the lookout for “sneaker waves”. Sneaker waves are defined as a very large, powerful coastal wave that approaches the shore suddenly and unexpectedly. Injuries and casualties associated with sneaker waves tend to occur on sunny days because people are not on guard and are distracted enjoying the lovely conditions. Sneaker waves can definitely happen in poor weather, but usually, there may be a surf warning in place or gross conditions which deter beachgoers. If you’d like to see an example of a sneaker wave, check this footage (warning: footage may cause anxiety). Everyone was fine in this video, but the urgency is real. This is definitely a force of nature you don’t want to encounter, especially strapped into a loaded backpack.

KRNCA was my first foray into hiking through an intertidal zone. The LCT (northern section) actually contains three intertidal zones. An intertidal zone is defined as the area where the ocean meets the land between high and low tides. Planning our entry into the intertidal zone ended up being a late day affair as our other option was embarking in the wee hours of the morning (like 3 am). After checking our tide charts once, twice and assessing the conditions, our volunteer group descended into the most southern intertidal zone (~4 miles). Despite being anxious beforehand, once we were down and moving, it was a very pleasurable and visually stunning experience. We decided to hike the entire zone (~4 miles) to the end as to reduce our next day’s mileage.

The KRNCA is a constant supply of fascinating sights, compelling views, and abstract moments. By doing our project in April we aligned with the wildflower season. We saw Indian Warrior (Pedicularis densiflora), Inside-out Flower (Vancouveria planipetala), Cobweb Thistle (Cirsium occidentale), California Oat Grass (Danthonia caliornica), and much more. We listened to different birds (Scrub-Jays, American Robins) wake us up in the morning, coyotes exchanging stories in the dead of night, encountered huge black bear tracks in the intertidal zone, and sadly walked by a sickly Pacific Harbor seal. When exploring tide pools we came across Giant Green & Aggregate Anemone, Purple Sea Urchins, Ochre Sea & Leather Stars, Giant, Black, and Lined Chiton. Participating in this project was a 24/7 sensory delight and something I will never forget.

While a “beach hiking project” can come off as dreamy, the reality is that the KRNCA project is aptly labeled challenging. Although the daily mileages involved aren’t really long and there’s no real elevation gain or loss, hiking the LCT is a demanding but extremely rewarding journey. While a good portion of the LCT is on what you’d consider “normal trail”, a good portion of it is on the beach. Hiking on the beach means negotiating what sacrifice you’re willing to make: river rocks, tiny pebbles, or deep, dry sand. Each surface challenges a different part of your feet and legs; it can also aggravate any past or quietly lingering injuries.

If that’s not enough, snagging a permit to hike the Lost Coast Trail has become increasingly difficult each year. The popularity of this region and trail has grown in the backpacking and entry thru-hiking stratum. While day use is free and doesn’t require a permit, during the high season (May 15-September 15) there are 60 permits. During the low season (September 16-May 14) there are only 30. These permits are for the entire King Range National Conservation area, in which there are plenty of other trails available for public recreation besides the LCT. Upon returning back to Flagstaff, I ran into a younger couple with a “Lost Coast Trail” sticker on their Nalgene. I told them I had just returned from working/hiking in that area and told them how much I loved it. They said they had lived outside Shelter Cove for over two years and could never snag a permit to backpack the LCT. We are… so lucky.

I truly believe the pictures from this project will do the talking. Please visit the KRNCA photo gallery! You can also visit the BLM’s Flickr account which also has some sweet imagery! If you have any questions about this project, feel free to email me at aidalicia@wildernessvolunteers.org